By Socrates Mbamalu—

Kelvin and I return to Ile-Ife after spending some time at Ibadan, where we had a sort of residency in my grandma’s house, reading and writing and exploring Ibadan. Getting to Ile-Ife, the ancient city where the Obafemi Awolowo University is located, a school we both attend, we go to Kelvin’s house, which he shares with Babajide Olatunji. I’ve heard so much about ‘Jide, most especially about his drawings. School is closed and ‘Jide has travelled to Akure, to visit his family.

‘Kelvin, what of ‘Jide’s artworks you were to show me?’ I ask.

“He won’t be happy with me for doing this but let me show you.”

Kelvin brings out a brown paper used to wrap the drawings. He carries them like delicate diamonds.

“It’s just a drawing,” I tell him. His look is enough reply to my statement.

He brings out one of the portraits and the first word that leaves my mouth is, “Fuck!” I stare at the drawing in front of me. Kelvin seems to enjoy the way I am dumbstruck. The drawing is that of Gina. It’s a portrait. But Kelvin is not done. He shows me another drawing Jide made when Nigeria had its fiftieth independence celebrations. It’s a drawing of fifty matchsticks. I realize that I have seen some of these drawings on Kelvin’s blog, but I thought they were pictures.

Sometimes you meet a work of art before you meet the artist. But because that work of art makes an impression on you, you feel you’ve met the artist. That’s how I felt about Jide and his work.

I get to meet Jide. Upon consequent meetings, I realise he is always on shorts, a short-sleeved shirt, and well-combed afro. Sometimes, a comb is perched on his hair. When working, he has an earphone plugged into his ears. Most times he is either listening to some jazz by Spirogyra, Dave Brubeck and Miles Davis, or Yanni, Mozart or Bach. With music he is on another plateau where everything else is zoomed out and blocked off, and the only focus is the drawing. He can’t work with noise.

“Noise distracts me,” he says, “I won’t be able to concentrate.”

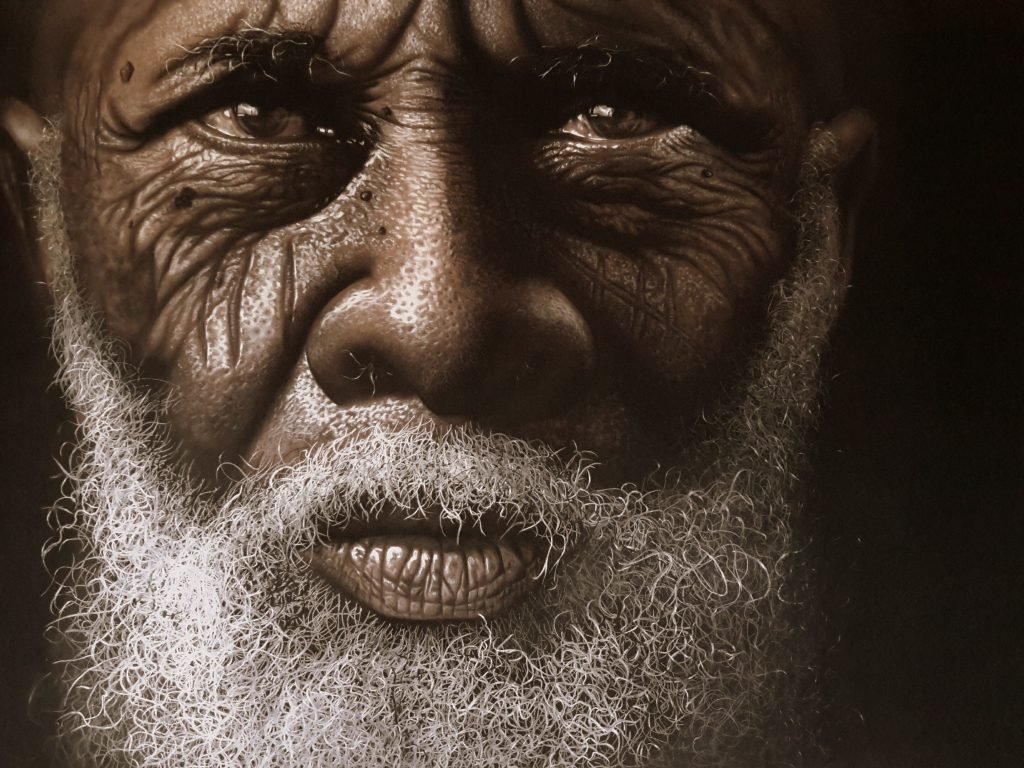

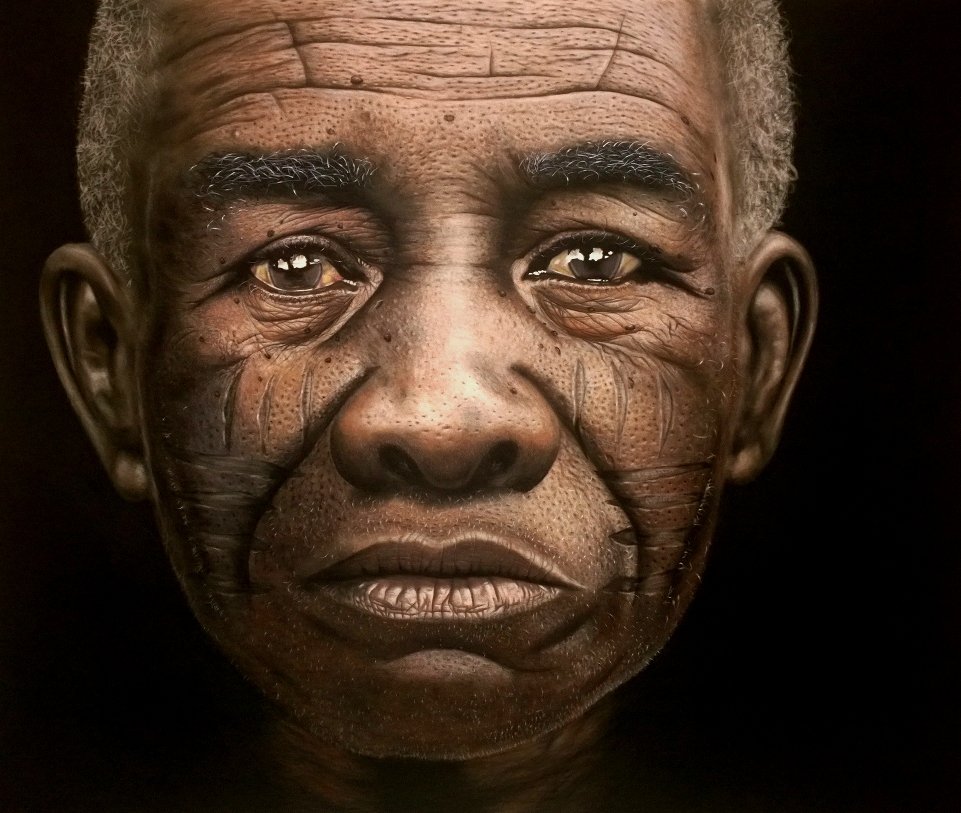

For the delicate process of bringing life to paper, Jide needs silence. This is still when he is in a one bedroomed flat, and the noise from neighbours distracts him. An early riser, he sits at the table near the window. After scrolling through his laptop, perusing some images for tribal marks, he settles to draw. This drawing is for Tribal Mark Series I, a series that elongated into two and consequently might continue into five.

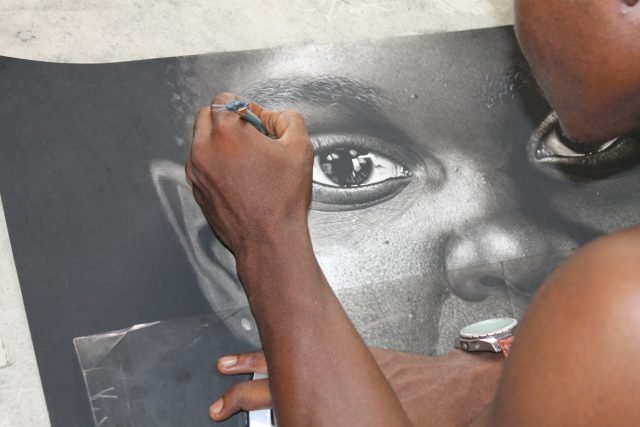

I watch him as he draws. He shades. Drawing a part at a time, like unravelling a mystery. Sometimes he starts with the eyes. Other times the lips. He is using coal and all his fingers are blackened. In the mornings when Jide doesn’t want to draw, maybe uninspired, he walks round the ancient city of Ife only to come home later in the day. There are occasions when Jide interacts with the locals, especially when carrying out a research on a project, in this case, the Tribal Mark Series being exhibited in London, at the TAFETA Gallery.

One day, lying down in my room on campus, Kelvin asks me to come over to where he and Jide stay. “Jide just completed a drawing. You have to see this.” I get into a bus quickly. I get into the house and Jide’s new work stares at me: a beautiful girl with scarification marks at the side of her head. The tribal marks on her are found among the Igbos, so we call the girl Oluchi. We chat and eat and discuss the drawing and the next work at hand.

Jide comes across as quiet and reserved. But upon knowing him, you realise the shyness is just a coat he wears. He has a very good knowledge of the Yoruba language and culture. His English is just as crisp and fluent. It’s hard to decipher how he feels about things. It’s difficult to know if he is angry. But Kelvin seems to know when Jide is angry or not, when he is uncomfortable or not, when something is troubling him or not.

In the small room Jide and Kelvin share, the wall is occupied by two large drawings. Jide is now doing bigger drawings for the Tribal Mark Series II. These are pastel drawings. And because of the demand of the tribal mark drawings from collectors, Jide needs to work faster. Jide tells me, “I draw for eight hours, sometimes more. When I read of how Picasso always stayed in his studio drawing, I knew I still had a long way to go.’

Some days after, Jide rents a bigger house with three bedrooms. He converts one of the rooms to his studio. On the door is a warning: “Trespassers will be shot. Survivors will be shot again.” I realize that all the while, he might have been uncomfortable with the number of people that visited his small room. I call to inform him that Kelvin and I are coming, and we fix a time. The new works in the new house are as big as 60 x 96 inches.

“My studio is very sacrosanct. I don’t like people seeing my uncompleted works,” Jide tells me. I peep from the door of his studio and see two completed drawings. “I’m not yet done with those works,” he adds. When drawing he doesn’t leave anything out. When drawing the portrait (character) Jide takes into consideration, whether the character is happy or sad, facing sunlight or not and such details. He simply doesn’t draw from photographs. I ask him why.

“Drawing from photographs has made many artists lazy. I used to wonder how those artists, Da Vinci, Titian and Caravaggio, how they used to paint from life and models. I once watched a documentary where they talked of how Da Vinci was painting the last supper and he would go to the market place to look for the character of Judas. He looked for the perfect face of Judas and couldn’t continue painting until he found it . . . there are times when I’m working on a portrait and I’ve told myself how the mouth is going to look. But when I go out and see somebody’s mouth that fascinates me, I change my thought.”

I would have thought that writers were the only ones involved in characterisation, but the background details Jide gives to all his drawings tells you a lot about the effort and time he takes before starting to draw. This reflects deeply in his work: a sense of purpose and direction. In one of our conversations he says, “The artists that I looked up to had the skill but there was no purpose attached to the skill. Skill isn’t enough, and I don’t believe in talent. I believe in hard work. They had the skill but the purpose was just to show how good they were. Not to leave something for others. Not a legacy. I don’t want to be someone that just keeps drawing portraits of public figures and I am only remembered for drawing portraits. Besides showcasing my skills, what more have I done? I want whatever I create to at least speak to one person in the world anywhere. Someone can relate with it. I don’t want to create something where they say, ‘wow this is beautiful.’ ‘Look at all those lines!’ And then you go away and forget what you saw. I want to create something that is striking. Something you stand in front of and then you can’t leave because there is so much to absorb, so much to see, so much to relate with. I want you to stand in front of something and it speaks to you. It stimulates thoughts in you.”

Jide started drawing in primary school, and he knew he would do one thing, draw. He studied Botany at the Obafemi Awolowo University. While studying, he drew to make money and improve on his skill.

“I would download YouTube videos. Spend nights in cyber cafés and browse. And during that time Internet data was expensive on phones.” Being a self-taught artist is one thing, but being very good at what you do without any training is another. But Jide doesn’t think it is all talent.

“Hard work, I believe in hard work. Talent is not enough.”

It is no surprise then when Jide says, “I’ve not achieved anything yet. I’m still growing.” This is despite being the youngest artist, twenty-four at the time, to be represented by TAFETA Gallery in the UK and also having his works showcased on an international level, in places such as the 1:54 Art Fair in New York City and also in the UK apart from local exhibitions such as in Lagos that had his work sold out.

Jide and I get into a chat about artists he admires when he pulls his phone out and shows me a drawing by Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, “Look at how anatomically-correct David draws the hands and legs of his characters.” There is a sense of excitement in his voice. Then he says, “The picture got me thinking to the extent that I couldn’t sleep. It just made me realise how inadequate I am and how long I still have to go.” On the ceiling of Jide’s bedroom are the pictures of Michelangelo, Vermeer, Ingress, Caravaggio, Gerald Gericault, Picasso, Titian, Goya, and Picasso. He put the pictures there to stare directly into the eyes of the artists every night before he sleeps. He reminds himself that he has not achieved anything, despite the international circulation of his works.

His agent, Ayo Adeyinka suggested the title The Book of Proverbs for Jide’s next project which involved pictorially representing Yoruba proverbs. But due to the fact that many art collectors wanted to buy more of his work for the Tribal Mark Series, the project had to be paused. There is a lot of Yoruba culture inflected in Jide’s drawings. Many think they are drawn by a middle career artist. In many of the conversations I have had with ‘Jide, he always makes recourse to the Yoruba tradition and culture and how he sees his drawings as a way of cultural preservation. The scarification marks for example is a prominent feature in the Yoruba culture, and this fading practice is dying with modern times. ‘Jide sees it as a duty to represent these marks in his drawing, ‘a time will come when my children will not know what scarification marks are because it might not be common during their time. These drawings might be the only thing that would help them.’ Asides that, his pictorial representation of Yoruba proverbs is one that goes a long way and it is easy to see how most of the ideas on what to draw revolve around projecting the Yoruba culture and tradition he’s grown up in.

“It takes anything from four weeks to six months to complete a work,” Jide says. To my question of what next, he replies, “I’ll keep drawing till I drop dead.”

Socrates Mbamalu is a writer with his works published in various online magazines.

All images courtesy Babajide Olatunji.

Readers like you make the work of Saraba possible. Donate.