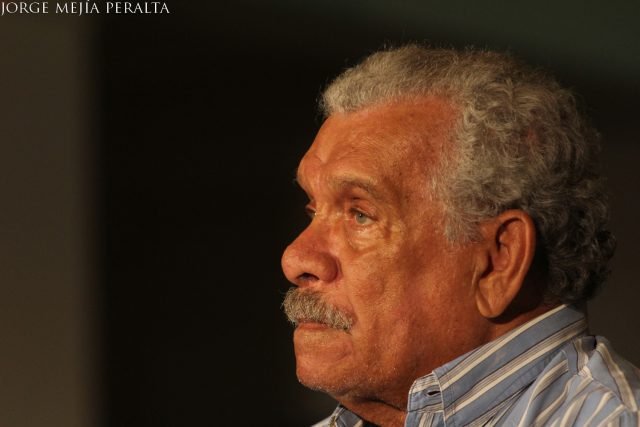

A few deaths have rocked my world lately – notably Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Umberto Eco – but none felt so personal as Walcott’s. The first instinct, after the shock of Akin Adesokan’s retweet of Jeanne-Marie Jackson’s tweet, was to find the YouTube video of the Walcott interview with Christian Campbell, in which he read “The Light of the World,” starting with the epigraph from Bob Marley—“Kaya now, got to have kaya now, /got to have kaya now, / for the rain is falling.” His voice had that unmistakable lilt; he owned Marley, owned the lyric and the song, owned every stretch of the Caribbean. And he was a leading light of the world.

I first read about Walcott in 1992, on the pages of Weekend Concord, in an article probably written by Mike Awoyinfa, shortly after Walcott won the Nobel. There was a reference to his majestic verse and devilish ways: “I’m beginning to feel like the beast of Boston,” he was quoted as saying. There was a poem titled “Miramar,” which was different from anything I had read up until that time. Thereafter came the drama (Dream on Monkey Mountain, staged one of those undergraduate nights at the University of Ibadan Arts Theatre) and the essays. Kole Omotoso has argued, quite persuasively in a posthumous tribute, that Walcott was an even greater playwright than poet, but Walcott for me, as for many, was the Poet.

Studying him chronologically has been a labour of love, from the collections he published in his thirties (In a Green Night, The Castaway, The Gulf) and forties (Another Life, Sea Grapes, The Star Apple Kingdom) to his fifties (The Fortunate Traveller, Midsummer, The Arkansas testament), culminating in Omeros, the “epic of the dispossessed,” easily one of the top ten volumes of poetry existing in human civilization. Only in the last year have I allowed myself to touch the ones that came after—Tiepolo’s Hound, the Prodigal, and now, finally, White Egrets. Reading White Egrets posthumously these last couple of months, one is struck by the foreboding in some of the poems, a clear sense that the author was coming to terms with imminent mortality. “In Amsterdam,” a poem I earlier had the pleasure of listening to Walcott read on YouTube, heightened by images of the city, now assumed new meaning –

I want the year 2009 to be as angled with light

as a Dutch interior or an alley by Vermeer,

to accept my enemy’s atrabilious spite,

to paint and write well in what could be my last year.

He did survive 2009, lived eight more years after that, though in poor health. I like to think he was triumphant. Triumphant, because in a career spanning close to seven decades he had created a corpus surely as majestic and timeless as the Arch de Triomphe, and his final collection put a stamp on that. In White Egrets there is no straining for meaning, no anxiety of influence. There is only a poet who has dwelt so intimately with this entity that is his Style, his Voice, that he and the Voice are one and the same, like an old griot and his rocking cane chair are one. This collection, published in the year the poet turned 80, gives a sense of recapitulation. There are stock Walcott themes like empire, in poems like “The Lost Empire” and “The Spectre of Empire.” There are elegies for friends like Aime Cesaire. There are several poems about place—“Barcelona,” “A London Afternoon,” “In Amsterdam,” and “In Italy,” first encountered in The New Yorker: “I have come this late/To Italy, but better now, perhaps, than in youth/That is never satisfied, whose joys are treacherous.” Walcott was conscious of being a traveller—a fortunate one, in spite of identity crises—through time and space.

There is of course also love, requited and unrequited. The middle-aged poet of “Light of the World” wrote with a tinge of regret about the beauty humming along as Marley rocked from the transport radio, his artist eye tracing the spread of light on her black skin—“O Beauty, you are the light of the world!”—he thought, concealing a tear as he departed from the transport. Perhaps unconsummated love yields sweeter poetry, with the sense of lost opportunity. But what does love do to time? What does time do to love? “Sixty Years After” is a poem about an encounter with a truly old flame:

In my wheelchair in the Virgin lounge at Vieuxfort,

I saw, sitting in her own wheelchair, her beauty

hunched like a crumpled flower, the one whom I thought

as the fire of my young life would do her duty

to be golden and beautiful and young forever

even as I aged. She was treble-chinned, old, her devastating

smile was netted in wrinkles, but I felt the fever

briefly returning as we sat there, crippled, hating

time and the lie of general pleasantries.

Finally, there is also “Forty Acres,” written for Barak Obama—“A young negro at dawn in straw hat and overalls,” ploughing the furrow of his “cotton-haired ancestors,” before “a tense/ court of bespectacled owls…a gesticulating scarecrow stamping with rage at him.” It would have been interesting to hear what Walcott, the student of Empire, would have had to say about the crass whitelash that has followed the Obama presidency.

Lately, I have been working through Ogaga Ifowodo’s doctoral thesis, in which he deals with the relationship between colonial trauma and black literature, in texts such as Wole Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman, Toni Morison’s Beloved, and Derek Walcott’s Omeros. In this masterful narrative—if we can call a doctoral thesis that—Ifowodo elegantly weaves three black literary icons (one African, one African-American, one Caribbean), each represented by their signature works, spanning the three genres of drama, fiction and poetry, into one global representation of blackness, trauma, and the postcolony. Ifowodo does as well as any to situate Walcott within the postcolonial narrative.

It has been a pleasure also to read other critical responses to Walcott’s poetry, from the love of peers like Seamus Heaney (“The Murmur of Malvern”) and Joseph Brodsky (“The Sound of the Tide”) to the near-condescension of otherwise revered critics like Helen Vendler. What is undeniable is that through his body of work, Walcott’s voice grew from the early Caliban who mastered the language and poetry of Prospero more than its owner, through the mid-career American prism of Wallace Stevens and Robert Lowell, through the plunder of the treasures of Western civilization in Omeros, to the ageless, unrelenting hound of history in his later works, with a voice inimitably his, a voice both cosmopolitan and rooted in the landscapes (and seascapes) of home, the landscapes within. He made history personal, the personal historical, and poetry out of both polarities: “For every poet, it is always morning in the world…History a forgotten, insomniac night; History and elemental awe are always our early beginning, because the fate of poetry is to fall in love with the world, in spite of History.”

God rest ye merry, gentleman.