Aunty Aggy swatted flies from the pyramid of tomatoes she was trying to sell, the ones at the bottom resting in a soupy mess of imminent rot.

“Ah, madam! This one kaa worry! Everything is fresh, just for you!”

The effort of forcing pleasantries over spoilt produce had begun to take its toll. What she thought was a convincing smile looked to her customers like a masquerade’s painted emotion, her skin pulled back so tightly on so many occasions that it appeared to be folding in on itself when it was at rest. She rocked backwards on a wooden stool too small for the spread of her hips, her legs straddling a gutter bulging with sand and shreds of plastic bags. Aunty Aggy enjoyed the private delight of knowing that the shoppers had no other option but to buy from her; all the other vendors had kept their vegetables decaying in the sun just as long as she had and most were selling at even higher prices.

“S-s-s-s- so madam! How much do you want?” She scratched the base of her neck absentmindedly. It was probably just the beginning of a sore throat. Big Man looked at the neat crack on his gold iPhone’s screen–would have to send Small Girl to buy him a new one, one more befitting of someone of his stature–but now, to call Small Boy and put him in his place.

“My friend! What nonsense report is this? When I say we have to cook the numbers small, what don’t you understand?”

Big Man coughed halfway into his tirade, Small Boy sputtered feeble excuses for his unwarranted honesty–then silence. There must have been some interference with the line. There was a studio across town, hidden behind so many trees and shrubs that those who didn’t know of its existence mistook it for an abandoned Parks and Gardens project.

Inside, a journalist wrapped up her afternoon broadcast after reports on the latest ‘unprecedented’ pipe-laying initiative in a district not as far from the city, as city people would have liked to think.

“I’m Awa Idris, and you’re listening to the news at four on Uniiq FM. Her voice came out in scratchy disjointed bursts, interspersed with the emptiness of white noise and strange beeping sounds. The presenter attributed the blip to one of many malfunctions of the station’s ancient equipment. Irritated listeners adjusted the knobs on their dashboards and knocked the speakers on their handheld radios.

“Ah these people paaa! Nuna switched off the radio sitting on her desk, teetering on a pile of scrap paper. It wasn’t surprising to lose signal in this office; it was one of the quirks of working in the Old Parliament House. When the ever-breaking wave of meaningless administrative work and phone calls from the head legal counsel throwing orders down receiver had subsided, she would daydream about the spectres of Kwame Nkrumah and Ghana’s other founding fathers– she assumed there had been mothers too but perhaps the history books forgot to mention them by name– arguing next door in the old chamber, their voices muffling and interrupting the invisible waves of sound shooting from broadcast masts through radios and phones. Now, all she could do was hope to finish the last hour of her workday in silence, only if Quaye didn’t launch into one of his incomprehensible lectures about the legal process in Ghana and that one time he sat in on a very controversial Supreme Court case.

“There are all kinds of things going on in this Accra! Who is going to stop it?” Quaye waved his hands in front of his face frantically, as if he expected Nuna to be able to find the remedy for the sickness he believed was inching its way through every channel and cavity of the country’s administration and operations.

“Everyday, speech, speech, press conference. Talk is too cheap nowadays!”

“Quaye, I hear you. But if I don’t finish editing these minutes before 5, you know how he is…”

Nuna watched him push his glasses back up his nose, shaking his head, as if to show disappointment in this girl he took to be harmless enough, albeit a little simple in her contentment with being just another bolt in a machine that was being taken over by rust. His judgment wasn’t lost on Nuna, but she was too busy wondering why it was that Ghanaian men of a certain age– at least all the ones she knew– all wore the same gold-colored glasses with thin frames tipped with tortoise shell and circular lenses.

The day’s end crawled into view, and tired civil servants filed out of the gates of the Old Parliament House, trying to shake a day’s worth of boredom and bureaucracy off their clothes as they went along. Nuna crossed gingerly through four lanes of traffic; two heading towards the jumble of colonial buildings and wooden structures that was Jamestown, and two heading towards the relative serenity of home, to catch a trotro. The usual discord of traffic noise was choppier than usual. It was as if the sounds of car horns and angry drivers hurling threats at each other through open windows were being cut off before they reached completion. Yet, Nuna’s attention was focused on preparing herself to go ‘home’ for the day, to a place where discontent and envy were passed around the dinner table like heaped plates of rice.

She climbed into a cream-colored trotro idling by the road, its engine whining like an animal in distress, and squeezed herself into a window seat in the back. She had left Keta behind; the sly whisper of the sea at night, the sand that scorched her feet if she didn’t pick them up briskly enough when walking, the elusive neighbor everyone knew only as Mama with her orange beads and folk tales about Mawu who gave birth to the world with one snap of her fingers and placed language on the tips of humanity’ tongue like pieces of fluffy, freshly baked bread, stories always ending in the refrain:

“To nyatepe, do not tell lies.” Nuna had come to Accra to study and to find work, and was staying with her mother’s sister and her husband, both retired from the IRS, and their daughter, Yayra. Their one-story house hid behind a brick red wall, pink and white bougainvillea bursting over it and dropping dried leaves and petals onto the street. The unthreatening prettiness of the exterior belied the tension within.

“Ah! These patients will kill me oh! Another day of torture! ”

Yayra would expel a grand sigh, discarding her mask and making sure to pull her scrub trousers up to rest her legs up on the center table. One would think she had just performed heart surgery, and not spent her day assisting a dentist in extracting the teeth of small children addicted to sweets. Perhaps what exhausted Yayra was not her work, but rather the charade that blocked her family from discovering the truth. She had been fired from her internship after only a month. Her supervisor had little confidence that unsteady hands and an attention span that drifted in and out of focus could translate into a promising future in the dental profession. Yayra spent her days lounging on the back porch of a friend’s house until around 4:30 when she would walk back home practicing her tired sighs and don’t-even-ask eye rolls on the way.

“Sorry to hear that. What happened?” Nuna slapped the remote lightly against her thigh, as if the motion would somehow affect the shaky TV signal. She was trying to catch the news she had not been able to hear in the office between the radio’s buzz and Quaye’s chatter.

These staged interactions were a part of Nuna’s daily routine since she figured out almost immediately that Yayra had lost her internship. Nuna played along because it was an open secret in the family, and she would much rather trade fake platitudes with her cousin about how hard the working world was, than to referee the shouting match that would surely occur if her aunt and uncle decided to stare directly into the face of their indulgence towards their daughter.

It was much easier for Nuna to listen to Yayra’s imaginary anecdotes about fidgety children and drug kingpins with gold teeth, than to strip off her own emotions and lay them in front her cousin who was sure to give them only a cursory glance before absorbing herself once more in her own world. She found strength in silence, reserving her heart-to-heart sessions for early mornings before work, when she would rake a tail comb carefully through her short bob, speaking directly into the mirror:

“What’s next? Law school. Your own wig and gown. Your own notary seal. Your own law practice.” In the van, the nervous young man, around her age with a thin short-sleeved shirt and an ink stain blooming in his breast pocket, shook his right leg incessantly. Probably National Service personnel, overworked all month only to receive an allowance like a handful of change tossed in the face. He wiped his face with a handkerchief that may have started out its life as pale blue but was now streaked with brown.

“Have you been listening to the news today? There’s something strange going on with the phone signals in Accra. TV and radio too.”

He cleared his throat, scrunching up his face at the same time as if the act of speaking was causing some sort of irritation. Nuna gave him a distant smile, one of those that revealed no teeth, hoping to convey as politely as possible that she wasn’t in the mood to exchange small talk with strangers.

Usually she was very generous with conversation, especially when the shrillness of the other person’s voice hid a certain desperation for human interaction. Mawu only knows, she spent a long time listening to both sides of her aunt and uncle’s arguments, always shifting beneath their steady gaze because she felt this was information she could do without. At least in this case, the young man’s unease would last for her only until she reached her stop.

“Yes, I noticed. I’m sure it’s just the rain affecting wires and things. Nothing to worry about.” She smiled again, this time a little less tight-lipped in an effort to appear reassuring. It didn’t really seem to have worked. The occasional twitch of the veins on the young man’s thin neck showed that he had many more anxieties than she was capable of soothing.

Mawu didn’t consider herself a vengeful God. She was oddly introspective in a way that may not be expected of an all-powerful, omnipresent entity. She was just and harsh when she needed to be, and so despised the ridiculous representations that depicted her either as a benevolent mother who strapped children to her back with Ewe kent, or as a crazed, fire-spitting woman embodying the irrational imbalance supposedly characterized by a woman’s gender. Most of all, she found it hilarious that no one knew she was really the one in charge, that in their daily lives human beings confined her to parts of their children’s names or exclamations of shock or disgust.

Mawu! She often saw clocks, calendars and framed posters depicting a pale man she didn’t quite recognize, with mournfully upturned eyes and long smooth brown waves tumbling past his slim face. She could not contain her laughter. Claps of thunder and lightning would result while her attendants watched in amazement and with a healthy amount of terror. Her misguided human subjects simply called it the rainy season. Apart from the accidental storms brought on by her raucous sense of humor, she did not put on extravagant displays of wrath, preferring to place subtle hints close enough to the people she wanted to warn. When she began to see city dwellers discarding the truth like used rags; tossing lies back and forth in parliament, signing falsified documents, spewing meaningless compliments to appease both wife and mistress, she started thinking of what changes she needed to make.

Mawu stood on the veranda of her little house in Keta. It was exhausting really, to have to watch human beings repeat the same mistakes over and over, since the world’s inception, especially when they loved to pretend like they knew what they were doing.

“Nyatepe! Fafa! One of you, bring my radio!”

Mawu’s attendants burst through the screen door in their haste to obey her. Their zeal should’ve taken it off its hinges, but in Mawu’s house nothing ever fell apart because she could mend it before it thought to do so. The radio was a small silver contraption, with numbers painted on in black, and a red and white arrow pointing to the frequency. On the top right hand corner, next to the dial, the words BBC AFRICA were stamped on, also in black. Mawu always got a little chuckle out of this. If for nothing else at all, the British were good for radio.

“Let’s see what this man has to say today.” She turned the dial to a station broadcasting the State of the Nation address. Nyatepe and Fafa stood side by side, their slim hands clasped behind their backs, mouths almost hanging open in awe of Mawu’s godly presence. It had been more years than they could count, even if their childish frames did not show it, but they still couldn’t help but admire Mawu’s strong black hair, with extra sheen added by the thread she used to style it, her broad muscular back and arms that dared anyone to do wrong only so she could show them the error of their ways with a shake or a slap. It did not even cross the attendants’ minds to contemplate how odd it was that the Supreme Being would still be eager to hear what humans had to say when she already knew their every artery and vessel, and understood all their desires and weaknesses.

“I am beyond proud to be the leader of a country as great as this, one abounding in promise and opportunity for the future. Ghana will continue to rise, a shining black star, a beacon for our neighboring countries and for the rest of the world…”

Mawu snorted. “Shining black star. I should never have given them the idea to use that as a national symbol. If I have to hear that one more time!”

“Yes Ma. Not that you make any mistakes!” The attendants nodded so vigorously that their braided buns unraveled and fell forward, slapping their foreheads with each nod. The President continued, in a voice that seemed to boom out from a puffed up chest:

“The people’s interests have been at the forefront of this administration. We have constructed roads, schools, hospitals and improved sanitation systems in rural and urban areas. Above all, this government has aggressively pursued a zero-tolerance policy against corruption. Honesty and transparency are the order of the day.”

At this point in the speech, Mawu threw her radio down into the flowerbed next to the veranda, the President’s voice now crackling and fading from within the lush bushes of purple roses and yellow hibiscus.

“Honesty and transparency. These Accra people have misused my words for long enough. What should I do with them?”

Nyatepe lived up to her name, and so was always on the side of upholding the truth no matter the cost. Anyone who played with the truth– dividing it into more appetizing portions like aliha at wedding celebration– deserved retribution.

“Mawu, Mawulolo! Punish them. Let them know what it means to value the power of words. Let them…” Fafa interrupted, “Mawu, Mawulolo! May I speak?”

Mawu nodded. “I think you need to give them a chance, dzigbordi. Please, I’m begging on their behalf. Maybe give them some kind of warning?” Mawu fiddled with the heavy orange beads around her neck.

“No. I’ve been too subtle. Frankly, I’m bored with how clueless they are. It’s time to show them how much they are taking for granted. Every single person who has gambled with the truth will lose the words I have given them.”

Nyatepe’s face shone with smugness, while Fafa, always trying to slow the course of Mawu’s wrath, wrung her hands to the point where her skin felt as though it was burning. Fafa’s pleas persisted, “Please, at least spare those who never forgot your lessons. Me de kuku! Just consider it! Please…”

Mawu silenced Fafa with a threatening look.

—

Nuna walked down the dark corridor to Big Man’s office, her conviction firmly balled in her fist. Big Man could not possibly know that Nuna’s ears still rang from the chants of “To nyatepe, do not tell lies,” which Mama used to end her epic tales of Mawu and her boundless power to speak anything she wanted into being. Childhood stories about a deity everyone seemed to have forgotten helped her to keep her grip on integrity in a way that Sunday school coloring books could not. Tell the truth, me ga da alakpa o.

The ceiling fan in Big Man’s office ticked a regular rhythm as if to accentuate the importance of Nuna’s

refusal. “Sir, I can’t do that. If the internal auditors ask for our department’s budgets, I have to hand them over.” “Nuna, what is it you want? If you keep quiet about this, you can have whatever you want.” Beads of sweat dotted Big Man’s upper lip, threatening to fall off the side of his mouth and onto the mess of documents on his desk. Who was this too-known girl insisting on doing the “right” thing?

Nuna hoped that her nerves were not on full display, but she had no control over the irregularity of her breathing and the way it ruffled the frills of the collar on her new blouse. Nuna had no interest in plunging her head below the surface of murky waters where fiction became fact when it came from the mouth of the wealthiest person. She did not care about what she had to gain. A European car with an unpronounceable name and a driver who only spoke to say “Yes, Ma. No, Ma.” An apartment in a sterile gated community where only unfriendly expats could afford to live, identical houses nudging each other for space on land that once held one family at a time. Maybe even a first-class law degree without having to see a classroom from the inside or feed the ego of a lecturer in exchange for good grades.

Big Man glared at Nuna, the silence swelling around them. Suddenly, he realized she wouldn’t budge, but he had to try, one more time. And when he spoke, he was surprised to hear himself stuttering.

“D-do you realize what this scandal c-c-could mean for this office? If we are found to be playing with state funds…you know what? J-j-just go back to your office! I’ll call you if I n-need you!”

—

No one was aware, probably because they weren’t looking for anything bizarre, that a roaring silence was arriving to blanket the hum of Accra’s constant vibration. Not the Big Men, nor Aunty Aggy in the market, nor the journalists peddling the stories they were paid to tell. The change had been happening so discretely that people paid no attention at first.

It started as a gradual descent into silence, and its pace accelerated to match the drama and ceremony of the event. White letters began to peel and fall off the rear windows of trotros, and they now read things like” “O_ly G_d” and “N_ oman No Cr_.” Even this was easy enough to overlook; trotros were hardly known for being in good shape. Then signboards selling wax printed fabric, satellite TV packages and alcoholic drinks began to shed their text, their slogans, shredded into bits and pieces, rained down on stunned pedestrians, vendors and policemen who stood still on the pavements, immobilized by fear and wonder.

The Independence Arch proclaiming “Freedom and Justice” also lost its letters. They disintegrated in the air halfway down to the ground and their fragments crashed heavily on the roofs of cars and in the middle of roads, leaving dents and cracks where they landed. The noise broke through the windows of the Castle nearby, where the President’s aides were running back and forth through the office like ants being chased by repellent.

“Sir! Si_ We nee_ t_ declare a state of emer_ a st_ o_ Sir!” Phones were ringing with as much urgency as had filled the air of the office, their chimes cutting off halfway and falling silent. The President watched in disbelief as his party acronym and slogan slipped off the special commemorative cloth he had had made into his Friday shirt.

“Get me! Get me my advi___” Words were sliding off the pages of proposals, carefully worded contracts, confidential notes from one MP or another, leaving black flecks on the marble tile of the office. Outside in the streets, people screamed empty horror to the sky, and it didn’t matter whether they were in Kokomlemle or Madina, because all signboards bearing the names of neighborhoods were now rid off their bold white lettering, their blue backgrounds left as a mockery of what had just been present a moment before. Even those with the ability to sign their thoughts were rendered silent, their fingers twisting in unintelligible combinations before growing still, hands falling hopelessly to their sides.

Nuna was in the chamber of the Old Parliament House, where she preferred to take her lunch. This room had a kind of calm only possessed by sacred sites, compelling any visitor to quiet reverence in appreciation of the fact that history had been written on this very ground. She dusted off one of the red leather seats, surprisingly still free of cracks despite the fact that this room was hardly ever cleaned.

The current staff used it only as a path to reach the obscure accounts and internal audit offices that were housed in dark back rooms and could only be reached by walking through this space.

“Ghana, our beloved country, is freeeee forevaaaaahh!” She laughed to herself as her mock deep voice reverberated through the hall, striking the red and gold accents on the walls. It was silly, especially because she knew that Nkrumah hadn’t given this speech in this room, but rather to an enormous crowd not far from here, in what was now the Black Star Square where the Independence Arch stood. It must have been incredible to be a part of that crowd; swaying and screaming freedom in unison, with sweat and hope for the future prickling the skin at the napes of their necks.

She continued to chuckle at the irony of Big Men frantically trying to hide their misdeeds, especially in this office that had the singular purpose and power of underlining government corruption in red ink and forcing leaders to face the public they were cheating. She laughed harder at the thought of her aunt and uncle, hymn books held in mid-air every Sunday and lips pursed in perfect holiness singing: “Come my Way, my Truth, My life…” all the while knowing that they would rather willingly ignore Yayra’s deception than to admit to themselves and to nosy acquaintances in the church parking lot that their daughter could not hold down any kind of job. She wrapped her disillusionment in the empty plastic bag from which she had eaten her waakye, and headed back to her office, hoping that Quaye would be too busy to give one of his lectures.

She emerged from the silence of the chamber, to find the offices almost empty, with a few colleagues standing outside in the shade of the building’s overhanging façade, screeching and pointing at their throats, wild fear in their eyes. She approached one man she knew by face only– maybe a porter– and asked:

“Boss, what’s wrong?” She snapped her head back in shock as he turned his screaming mouth towards her and directly into her face. He didn’t seem to have heard her. Mawu! What was going on? From where she stood she could hear the chilling sound of metal crumpling and smashing against itself, and cars beeping non-stop as if someone had their hand nailed permanently to the horn. She looked at the flashing screen of her phone and realized she had received multiple text messages from her aunt, uncle and cousin. Each one said: “________________” the electronic rendition of the silent desperation that was raging around her in the street. She did not know that she was one of the few people in Accra who had not been denied access to their own voices. Hypnotized by the chaos spinning around her, she did not notice others like herself who stood still with facial expressions mirroring her confusion.

There was a woman standing next to Nuna who looked startlingly familiar with her thick orange beads and powerful shoulders. This moment of impossible recognition snatched Nuna out of the present horror and back to Keta; the bright yellow of the sand, the relentless waves that carried away the crumbling walls of the houses, the satisfying crunch of rocks under sandaled feet, Mama’s thrilling stories and her song:

“Tell the truth, do not tell lies.” The lyrics tumbled over Nuna’s head like leaves shaken off a branch, as the strange woman next to her kept singing and smiling as she sang.

“My dear, are you alright? Have you heard this song before?”

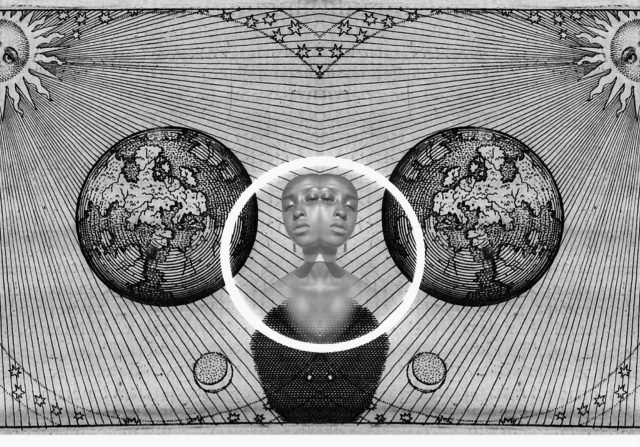

Image Credit: Isa Benn, used with permission.